Authors: Matthew Kelly and Alexandra Thorn (Curio Projects, Sydney)

In 2013 AHMS Pty Ltd (now Extent Heritage) completed an archaeological excavation at 478 George Street in Sydney’s CBD known as the ‘Mick Simmons’ site-after the famous sporting goods store which traded there until 2012.

The excavation yielded evidence of European occupation, from perhaps as early as 1813, through to the site’s last identity as the iconic sports goods store. During the usual post excavation artefact analysis several items, originally identified as building materials due to their size and form, were found to be anything but.

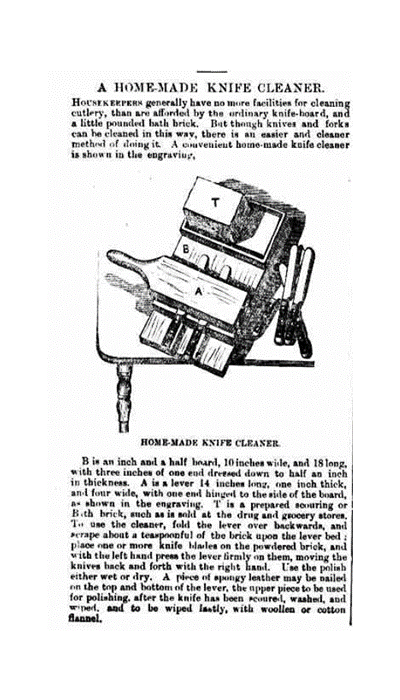

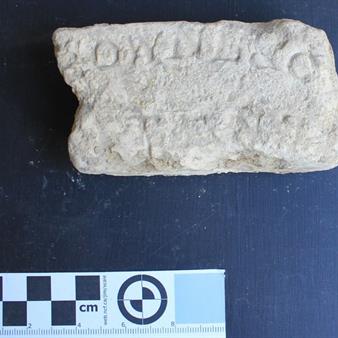

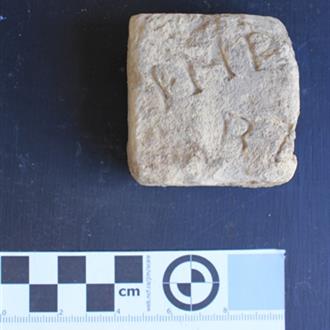

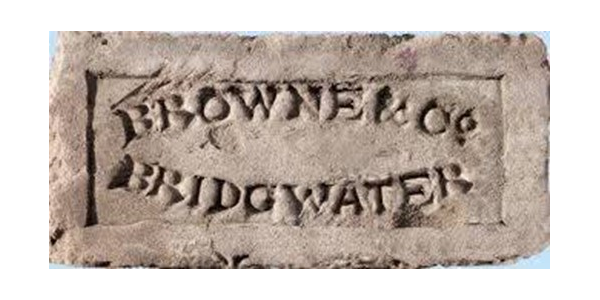

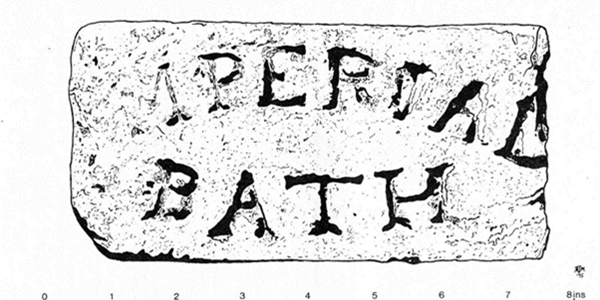

They are in fact ‘Bath Bricks’. They appear to be ordinary bricks, of similar dimensions and are usually impressed with maker’s names. However, they are not building materials at all but are domestic cleaning items used for scouring floors, and other surfaces, cutlery and other household items (photo 1). The dust from a bath brick, for example could be also used to create a substance known as ‘breeches ball’, for cleaning breeches and for shining boots. The altered bricks were also utilised as moulds for casting gears for machinery.

The bath bricks were manufactured at the small Somerset town of Bridgwater, already noted as a brick and tile manufacturing town. The first patent for the scouring bricks was issued in 1823 to John Browne and William Champion. The bricks consisted of a locally available mud, from the Parrett River, comprised primarily of alumina and silica particles, pressed into brick form, fired in a kiln to approximately 500-600°, wrapped in a paper cover and sold worldwide as a cleaning a scouring agent. Bath bricks were used worldwide, and another patent was issued in the US in 1865 to meet the desire to manufacture these ‘bricks’ directly for the US market. That patent notes that the US source material was discovered:

at Wood bridge, New Jersey, in large quantities, a pulverulent mineral of which a scouring-brick in all respects equal, and in some respects Superior, to the imported Bath brick can be made at a greatly reduced cost.

Several large fragments of bath bricks were found on the Mick Simmons site in a construction trench probably dated to around 1870 (photos 2 and 3). The examples at Mick Simmons were from Edward Sealy’s works manufacturing 1811-1839 and Browne and Co, 1840-1899, which later traded as the Somerset Trading Company. The site at George Street had traded as general merchants and grocery store between 1833 and 1870 under a number of owners – the earliest of whom was Frederick Gibson.

References

AHMS, 2016, 478 George Street Archaeological Excavation Report, for Amalgamated Holdings Ltd

Anon., 1855, The Footman, London, Houlston and Stoneman, pp. 27, 28, 37 and 48.

Adams, S and Adams, S, 1825, The Complete Servant, London, Knight and Lacey, pp. 366 and 392.

Murless, B, 1976, “The Bath Brick Industry at Bridgwater: A Preliminary Survey”, Journal of the Somerset Industrial Archaeology Society, v 1, p. 21

“Improved Scouring Brick”, US Patent No. 50,862, November 7, 1865.